Jan. 24, 2024

Is Third-Party Privacy Protection Policy Good for Business?

Many of us encounter third-party providers without knowing it when we are browsing the Internet. They are affiliated websites that collect user information and data gained from the primary website being used and are often necessary for many websites to earn profits by essentially selling user data, some even go as far as charging a user to access the site if they don’t agree to third-party utilization. It has been widely accepted that the downside of third-party providers often falls to consumers and their privacy, so much so that government policy has been implemented to notify and protect users. However, recent research by iRC faculty members has revealed an unexpected outcome of this type of policy for consumers and Internet users, as well as impacts to the websites and third-parties themselves.

Assistant Professor Hooman Hidaji, Ph.D.

Assistant Professor Hooman Hidaji, Ph.D., Assistant Professor Sule Nur Kutlu, Ph.D., and Professor Raymond A Patterson, Ph.D., along with co-authors, recently looked at impacts of third-party provider government policy. Their paper entitled Law, Economics, and Privacy: Implications of Government Policies on Website and Third-Party Information Sharing [1], was recently published in the journal Information Systems Research. The research discusses two types of government intervention policies meant to protect consumer privacy from third-party utilization: consent-based and website subsidization. Firstly, consent-based policies require that each website have a ‘consent-based’ disclaimer. For this type of policy, the user is given a choice to accept or decline non-essential third-party activity and is provided a mechanism to turn off unwanted cookies related to this privacy sharing. The European Union (EU) General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and the state of California as the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA) are both policies that require a user to consent to and be informed about a website’s third-party provider activity. Fines are issued to websites that do not comply. Secondly, website subsidization policies target websites that have stricter privacy concerns, such as public health websites and other government website interfaces. By providing government subsidies to the website directly, this policy prevents a website from needing to rely on third-party providers for revenue.

Selecting Third-Parties on a Website Under Consent-Based Policy (https://cookie-script.com/knowledge-base/consent-for-cookies), from Gopal et al., (2023)

Assistant Professor Sule Nur Kutlu, Ph.D.

The research team uses analytical modeling to examine how these two types of policies might benefit or impact users, websites, and third-parties, as well as resulting behaviours of each group.

Kutlu explains their initial findings, “Interestingly, we find that even though a consent-based policy may improve user surplus, in the absence of market entry and exit (a static market), it has the unintended consequence of increasing the number of third-parties and, thus, sharing of user information. We also determine that both consent-based and website subsidization policies may reduce competition by driving websites out of the market—to the detriment of user surplus and social welfare. To validate our analytical model’s findings, we empirically investigated the impact of a consent-based policy on third-parties in a natural experiment of the California Consumer Privacy Act. These findings raise significant implications for policy making surrounding online privacy.”

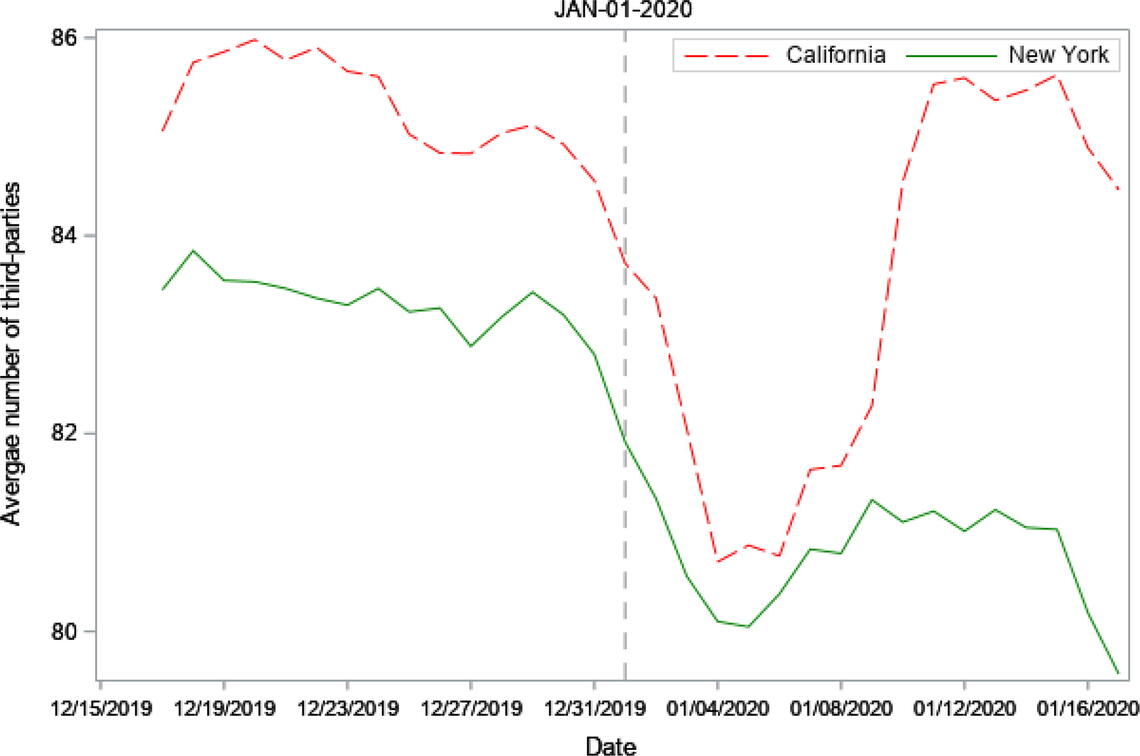

These additional findings are the result of the research team collecting third-party utilization data from two case studies as the CCPA was being implemented in California. They set up two different IP addresses in two different locations, one in the state of New York where the policy would presumably not impact data sharing by third-parties and the other in the state of California where there was a potential for the policy to impact third-party data utilization. Using these separate IP addresses, the research team then visited the same set of websites, 100,000 of the most-popular websites according to Alexa.com’s Application Programming Interface (API), and they recorded third-party activity.

The expectation was that the California IP address would see a decrease in activity after policy implementation. However, results show the opposite: while little change was seen in the New York case, the California case saw an increase in third-party activity after policy implementation versus before. That is, instead of the policy decreasing third-party provider activity, it appears to have increased activity.

Daily Average Number of Third-Parties, from Gopal et al., (2023)

But does this unexpected result mean that third-party privacy protection policy is good for business but bad for users?

As Kutlu describes, the implementation of content-based policies doesn’t always benefit websites or users, “Consent-Based policies where the number of third-parties are not under websites’ control are not beneficial to websites, as they decrease their revenue. However, consent-based policies are beneficial for third-parties, because users prefer to share their data with third-parties to avoid paying for content.”

Similarly, in the alternative approach, website subsidization, “policies decrease website revenues, and their effect on third-parties depends on websites’ comparative utility provision (aka quality of the subsidized website).”, says Kutlu.

In terms of which policy is better Kutlu states, “Website subsidization (policy) is similar to a scalpel, enabling policy makers to sculpt around and impact specific target markets. However, certain political and business forces may resist introducing publicly funded competitors, as they prevent a level playing field. Whereas consent-based policies are more comparable to a sledgehammer that uniformly affects all market segments. Policy makers can employ a non-profit website to focus on improving social welfare or user surplus in a highly specific market segment with website subsidization or to roll out consent-based policies that apply to a much broader set of target markets. For circumstances where it is difficult for the government to enact a law for the entire market, website subsidization policies are appealing alternatives, as they may provide even better user surplus than consent-based policies.”

Hidaji explains that there are two types of users based on how privacy sensitive they are and that companies (websites and third-party providers can use predictive approaches to take advantage of both,

“Some users see the pop-up and click ‘Accept’ without reading the terms, these are lower privacy sensitive users, most people are like that. Whereas others read the disclaimer and don’t click on ‘Accept’. The policy allows companies to differentiate between high and low privacy sensitive users and to increase their base for low privacy sensitive users (thereby) increasing the number of third parties, resulting in more third-party activity.”

However, removing third-parties entirely is also not necessarily the answer, as they can play an important role in site performance, provide more personalized experience for users, and improve user experience on the site in general. As well, removing third-parties altogether may increase costs for users in other ways.

Hidaji explains “If you remove third-parties then websites need to charge users, if they start doing that, then welfare decreases. Whereas now they are being monetized through advertising.”

In a more localized context, Hidaji notes that Canadian policy is moving toward this type of consent-based policy, as well as new approaches to data portability—the ability of a user to freely ‘port’ or move their collected data and information between companies and services. But overall, profit motives are essential to maintain a competitive market,

“Our model predicts that (consent-based policy) reduces profits of some players under some conditions and these policies situate a company at a loss, where the website makes less profit. As a result, those with higher costs may go out of business first, i.e., players that are making the least amount of money.”, states Hidaji.

Having users be more informed of both their different cookie options and of how their data is being used is a bigger issue, as Kutlu questions,

“How can we better inform users that their information is being taken? Going forward, policymakers can use our study to consider the different policy mechanisms at their disposal and choose which one works best for their specific context.”

[1] Ram D. Gopal, Hooman Hidaji, Sule Nur Kutlu, Raymond A. Patterson, Niam Yaraghi (2023) Law, Economics, and Privacy: Implications of Government Policies on Website and Third-Party Information Sharing. Information Systems Research 34(4):1375-1397. https://doi.org/10.1287/isre.2022.1178

Find more information about iRC research and activities here.