March 7, 2024

Recent Research: Critical IT Infrastructure and Coalitions

During the recent COVID-19 global pandemic, regions and nations around the world needed to quickly develop a way to re-start their economies as well as protect their citizen’s health and wellbeing. IT infrastructure—hardware, software, and interoperability specifications—played a crucial role in recovery while the pandemic was still raging, primarily through operationalizing a digital health passport system that allowed travel, access to services, and trade to re-start.

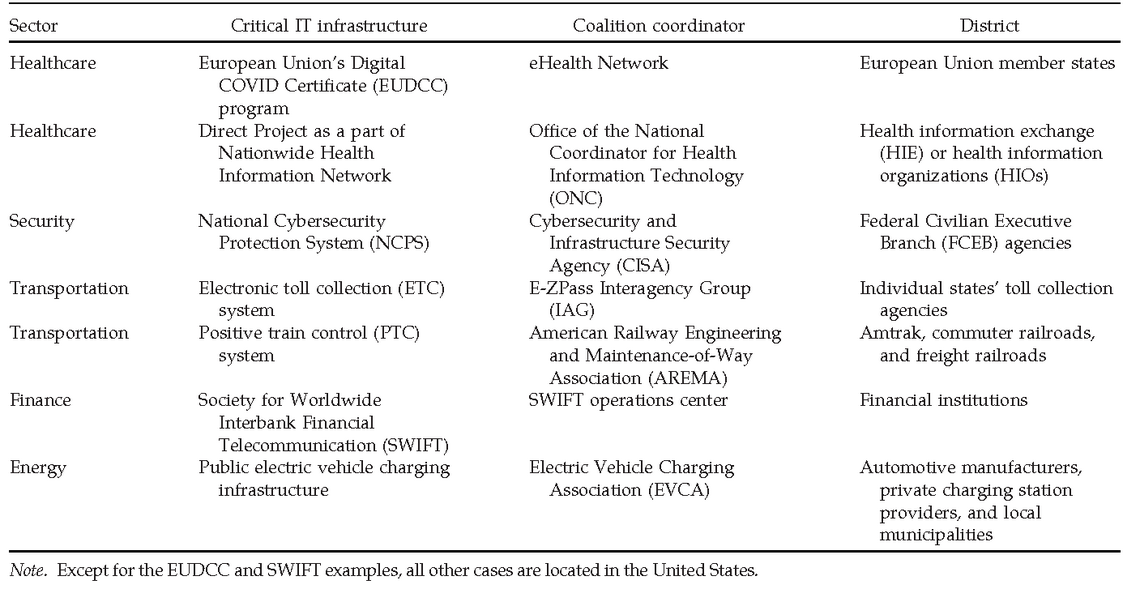

We use other forms of critical IT infrastructure daily, such as transportation systems, energy systems, and security. Deciding who adopts a critical IT infrastructure system, how IT resources can be shared, and how decisions are made about IT resources is the topic of the recent Information Systems Research (ISR) journal publication Join Up or Stay Away? Coalition Formation for Critical IT Infrastructure [1] co-authored by Arizona State University Professor Hong Guo, Ph.D., Northern Illinois University Associate Professor Yipeng Liu, Ph.D., and University of Calgary BTMA Professor Barrie R. Nault, Ph.D.

'Critical IT Infrastructure Examples' - Table 1 from Guo, H., Liu, Y., & Nault, B. R. (2023)

Whether they are districts, regions or nations, the size of the group that agrees to adopt the same kind of IT system is called a ‘coalition’ and is defined by the size of the group itself. Further, the nuances of joining or not joining can be modelled economically to better understand the benefits of sharing the costly expense of IT resources where benefits also include interoperable systems for a social benefit. Nault explains,

“If you join a coalition, (IT resource) decisions are made centrally, if you don’t join, they are made individually…. When there are multiple districts that are investing in resources for IT infrastructure, we want to understand how spillovers work, so that when one district or nation invests another district can benefit. And we look at the degree that they can benefit if they are working together in a coalition versus separately.”

One of the key features of being inside or outside the coalition is how decisions about IT resources are made.

“If you are outside the coalition, you decide about your own IT resources. If you are inside the coalition, you hand those decision rights to a centralized coalition coordinator who will determine what investments you need to make. The coordinator can look at the coalition as a whole and say, ok this district would invest a certain amount, this district should invest this etc…”

This is not the first time Nault has looked at IT infrastructure and coalitions. In the 2021 MIS Quarterly journal publication entitled Provisioning interoperable disaster management systems: integrated, unified, and federated approaches [2] Nault and co-authors discern how, in a coalition scenario, two districts might organize themselves differently within the coalition to share these resources. The current ISR publication grew out of this concept both by necessity and for real-world application,

“We were challenged in (the MISQ article) by scale, because if you only have 2 districts you are only given a choice of being in or out, but what if I have n districts, where does it stop?... It’s more complicated to understand a coalition that isn’t all in or all out because of the complexity in figuring out the joining part.”

Through investigating the varying sizes of coalitions, the authors came up with four possibilities: a singleton that does not join and makes their own resource decisions, a partial coalition where somewhere between 1 and almost all but not all districts join, a minimal coalition where just two districts join, and a grand coalition where all districts join. As an example of a grand coalition, the authors refer to the European Union’s Digital COVID-19 Vaccine Passport program, EUDCC.

“EUDCC was a grand coalition because all the EU member states joined. By joining, they basically agreed to follow the technical standards that the EU set. And what that meant was you had a health authority making decisions for what everybody needed to do.”

“But there were many non-EU members states that also adopted these standards and joined the coalition, and there were many countries that didn’t. The US didn’t say, oh I think we will adopt the EU’s approach to this, nor did Canada, we did our own.”

'Deviation of Equilibrium Coalition Structures from Socially Optimal Coalition Structures' - Figure 3 from Guo, H., Liu, Y., & Nault, B. R. (2023). Note. This figure is based on parameter values of n = 10 and κ = 0:35.

In the above scenario, the EU sets standards for the entire coalition and some centralized IT infrastructure was required but member states primarily integrated their own existing individual IT systems within the coalition while following EUDCC interoperability specifications. The article also discusses Health Information Organizations (HIOs) in the United States attempting to adopt interoperability standards to deliver healthcare more effectively across districts. Nault also describes an example not discussed in the paper, Provincial healthcare management in Canada,

“If we think about Provinces in a healthcare coalition, for example BC and Alberta have a formula (agreement) that says if you are outside of Alberta and you go to BC and see a doctor, that Alberta healthcare will cover the costs that are incurred in BC at a pre-determined rate. But I believe Quebec is not part of that coalition in the same way. Or think about if you go to a doctor in BC, they should be able to pick up a fair amount of your AB health record because of coordination between the provinces, I’m not sure that is the case for all provinces.

The idea is that if you are outside of the coalition, you don’t have quite the same interoperability (as being within a coalition).”

Though the benefits of joining a coalition are clear in examples like the EUDCC, the authors came to a surprising result: there is a state of equilibrium, or a scale of coalition, where it is not beneficial for everyone to join the coalition or where it is more socially beneficial to have a larger coalition than the benefits of the equilibrium anticipated for a socially optimal result.

“A social planner is not only including the value of the coalition, but they are also incorporating the value of those that have remained outside of the coalition; and if they should incentivize those that have decided to be singletons to join the coalition, so the coalition is bigger or vise versa.

“Let’s imagine that all EU countries joined the coalition except France. Then the EU social planner would decide if it’s better if France was in this coalition, and if it is (better) how are we going to make that happen?..Usually through a subsidy or a tax.”

Though equilibrium includes cost sharing for the coalition, the authors were not concerning themselves with the question of a balanced budget due to subsides or taxes for achieving socially optimal results.

“When we look at critical infrastructure, we are less worried about a budget balance, if the social planner has to spend money for the subsidy, we don’t have to cover that somewhere else because everyone is better off in the social optimal sense.”

[1] Guo, H., Liu, Y., & Nault, B. R. (2023). Join Up or Stay Away? Coalition Formation for Critical IT Infrastructure. Information Systems Research, 0(0). Published Online 23 Oct 2023. doi: 10.1287/isre.2021.0463

[2] Guo, H., Liu, Y., & B.R. Nault. (2021). Provisioning interoperable disaster management systems: Integrated, unified, and federated approaches. MIS Quarterly, 45(1), 45-82.doi: 10.25300/misq/2020/14947

Find more information about iRC research and activities here.